- Home

- Robert Graves

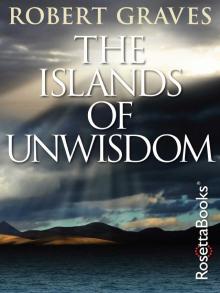

The Islands of Unwisdom

The Islands of Unwisdom Read online

The Islands of Unwisdom

Robert Graves

Copyright

The Islands of Unwisdom

Copyright by The Trustees of the Robert Graves Copyright Trust

Copyright © 1949 by Robert Graves, renewed 1976 by Robert Graves

Cover art, special contents, and Electronic Edition © 2014 by RosettaBooks LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover jacket design by Carly Schnur

ISBN e-Pub edition: 9780795336836

…la tragedia de las islas donde faltó Salamon: esto es, la prudencia. [The tragedy of the islands where no Solomon was found: that is to say, no wisdom…]

‘Varios diarios de Jos viajes à la mar

del Sur y descubrimientos de las Islas

de Salamon, las Marquesas, las de Santa Cruz, etc…. 1606.’

Contents

INTRODUCTION

1. THE BLIND GIRL OF PANAMA

2. AN AUDIENCE WITH THE VICEROY

3. THE VICAR’S BAGGAGE

4. DEPARTURE FROM CALLAO

5. WHAT HAPPENED AT CHERREPÉ

6. WHAT HAPPENED AT PAITA

7. ON THE HIGH SEAS

8. THE MARQUESAS ISLANDS

9. THE COLONEL SEEKS A HARBOUR

10. THE CROSS IN SANTA CRISTINA

11. SAN BERNARDO AND THE SOLITARY ISLE

12. THE ADMIRAL’S FAREWELL

13. GRACIOUS BAY

14. THE ERUPTION

15. A SETTLEMENT FOUNDED

16. THE COLONEL SPEAKS OUT

17. THE MALCONTENTS

18. A FORAGE WITH MALOPE

19. MURDER

20. THE ECLIPSE

21. THE SETTLEMENT ABANDONED

22. NORTHWARD ACROSS THE EQUATOR

23. HUNGER AND THIRST

24. COBOS BAY

25. THE LAST HUNDRED LEAGUES

26. AT MANILA

HISTORICAL EPILOGUE

MEMBERS OF THE EXPEDITION MENTIONED BY NAME

MILITARY

Don Alvaro de Mendaña y Castro, General, Leader of the Expedition, on board the San Geronimo galleon

Doña Ysabel Barreto, his wife

Don Lope de Vega, Admiral, his second-in-command, on board the Santa Ysabel galleon

Doña Mariana Barreto de Castro, his wife, sister to Doña Ysabel

Colonel Don Pedro Merino de Manrique, commander of the military forces

Major Don Luis Moran, his second-in-command

Captain Don Felipe Corzo, owner and commander of the San Felipe galeot

Captain Don Alonzo de Leyva, commander of the Santa Catalina frigate

Captain Don Manuel Lopez, Captain of Artillery

Doña Maria Ponce, his wife

Captain Don Lorenzo Barreto, Company-commander, eldest brother of Doña Ysabel

Captain Don Diego de Vera, Adjutant

Ensign-Royal Don Toribio de Bedeterra

Ensign Don Diego Barreto, second brother of Doña Ysabel

Ensign Don Juan de Buitrago

Doña Luisa Geronimo, his wife

Ensign Don Tomás de Ampuero

Ensign Don Jacinto Merino, the Colonel’s nephew

Ensign Don Diego de Torres

Sergeant Jaime Gallardo

Sergeant Dimas

Sergeant Luis Andrada, Sergeant-major of settlers

Juan de la Roca, orderly to Captain Barreto

Raimundo, orderly to Ensign de Buitrago, soldier

Gil Mozo, orderly to Ensign de Ampuero, soldier

Salvador Aleman, soldier

Sebastian Lejia, soldier

Federico Salas, soldier

Miguel Geronimo, with wife and seven children, soldier-settler

Melchior Garcia, soldier-settler

Miguel Cierva, soldier-settler

Juarez Mendés, veteran of the previous expedition

Matia Pineto, veteran of the previous expedition

NAVAL

Captain Don Pedro Fernandez of Quiros, Chief Pilot and master of the San Geronimo

Don Marcos Marin, Boatswain of the San Geronimo

Damian of Valencia, Boatswain’s mate

Don Gaspar Iturbe, Purser

Jaume Bonet, Water-steward

Don Martin Groc, Pilot of the San Felipe

Don Francisco Frau, Pilot of the Santa Catalina

RELIGIOUS

Father Juan de la Espinosa, Vicar

Father Antonio de Serpa, his Chaplain

Father Joaquin, priest in the Santa Ysabel

Juan Leal, lay-brother and sick-attendant

OTHERS

Don Luis Barreto, Doña Ysabel’s youngest brother

Don Miguel Llano, the General’s secretary

Don Andrés Serrano, his assistant

Don Juan de la Isla, merchant-venturer, with his wife

Doña Maruja de la Isla, his daughter

Don Andrés Castillo, merchant-venturer

Don Mariano Castillo, merchant-venturer

Elvira Delcano, Doña Ysabel’s Spanish maids

Ysabelita of Jerez, Doña Ysabel’s Spanish maids

Pancha, her Indian under-maid

Pacito, the Colonel’s page

Leona Benitel, his washerwoman

Myn, the General’s negro, veteran of the previous expedition

Introduction

Most of my readers will be as surprised as I was to find Spaniards trying to discover Australia and settle the South Sea Islands a generation before the Pilgrim Fathers landed at Plymouth Rock. This expedition, though it failed in its main objects, deserves to be better known because the Marquesas Islands and the South Solomons were discovered in the course of it, and because on the death of the leader, General Alvaro de Mendaña, his young widow Doña Ysabel Barreto1 assumed command of the flotilla and exercized the absolute power he bequeathed to her—a unique episode in modern naval history. But what has interested me most in the story is its bearing on the history of Spanish colonization. When the missionary spirit predominated, as in the Philippines, the natives benefited in the long run, despite governmental corruption; when precious metals excited the greed of conquest, as in the New World, they suffered cruelly; but when there was an irreconcilable conflict of motive, as on this occasion, they were abandoned (in the Spanish phrase) ‘to the claws of him who held them first.’

The story also explains why England, with a far smaller fleet, managed to wrest the command of the sea from Spain: her forces were not so rigidly organized. An English galleon was not readily distinguishable from a Spaniard, and had much the same armament; but the Spanish seamen, though they knew their trade well, only worked a ship and did not fight her, while the soldiers, who were the best-disciplined in the world, fought, but disdained to work her. Their naval and military officers were almost always at loggerheads, and the larger the vessel, the worse the mistrust and confusion. In the English navy the arts of navigation and war were closely co-ordinated, to the especial improvement of gunnery; the same men would handle sail or repel boarders, and the only rivalry was between commanders of sister ships.

I have not had to rely on English translations of the relevant documents. The first account of the voyage appeared in 1616, when Suarez de Figeroa included a carefully excised version in his biography of the Marques de Cañete, who had sponsored the expedition; and it was not until 1876 that the original anonymous report, from which he borrowed, was published in Madrid by Don Justo Zaragoza. What seems to be the only English translation of Zaragoza�

��s text appeared in 1903, under the title Voyages of Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, 1595–1606. The translator and editor was the then president of the Hakluyt Society, Sir Clements Markham, who possessed a wide store of geographical and nautical knowledge, but so little Spanish that he guessed at the meaning of almost every other sentence, and usually mistook it. A typical instance occurs in the starvation passage at the close of the voyage: Todo el bien vino junto, ‘All the good wine appeared too,’ which is almost in a class with Le peuple ému répondit à Marat, ‘The purple emu laid Marat another egg.’ No wine was, in fact, served to the men dying of thirst and the sense of the passage, which literally means: ‘All that was well came together,’ is that the general situation suddenly improved when the San Geronimo approached Corregidor Island at the entrance to Manila Bay.

Yet even in accurate translation this original report, which was largely inspired by Pedro Fernandez of Quiros, the Chief Pilot, makes difficult reading. It demands for its understanding a fairly comprehensive knowledge of the contemporary Spanish and Spanish-American scene, of late sixteenth-century navigation, and of native Polynesian, Melanesian and Micronesian customs. Moreover, the author, not caring to enlarge on some of the more discreditable episodes, often falls back on this sort of reporting:

Nine men were sent ashore to buy food. The business reached a point when Don Diego ordered an arquebus to be fired at a sailor who went up the mizzen-mast. The Chief Pilot advised Doña Ysabel that it was greatly to her advantage to finish the voyage in peace. That was a foolish affair, and so I will say no more about it.

or:

This was not the only false testimony borne by the malcontents; for another lie was told of another person. A friend said to one of them…

What lie was told, and by whom, or who the friend was, we are left to guess from hints dropped elsewhere.

I have done my best to reconstruct the real story, inventing only as much as it needed for continuity; and though I am on dangerous ground in accounting for the tense relations between Doña Ysabel and the Chief Pilot, something very much like my version of events must have taken place. The Vicar’s religious anecdotes are genuine, though condensed; and I have not had to invent names even for Doña Ysabel’s maids or the settler Miguel Geronimo’s children, Dr. Otto Kübler having recently found the real ones in the archives at Seville.

I must here express my thanks to Dr. Kübler, who first called my attention to the story and has kindly checked the opening chapters; to Don Julio Caro for lending me a copy of Zaragoza’s now very rare book Historia del descubrimiento de las regiones Austriales, which escaped the destruction of his library during the Spanish Civil War; to Robert Pring-Mill for research at Oxford; to my neighbour Don Gaspar Sabater for placing his Spanish encyclopaedia at my disposal; to Gregory Robinson, a leading authority on Elizabethan seamanship, for correcting my nautical errors; to Kenneth Gay for constant help with the novel at every stage.

R.G.

Deyá,

Majorca, Spain.

1949.

Chapter 1

THE BLIND GIRL OF PANAMA

In the visible firmament which (according to my learned Sevillian friends) is but the eighth of a grand series—the other seven being designed only for the reception of saints, martyrs and their attendant angels—God has placed many thousands of stars. Some are great, some of middle size, some so small that only the keenest eye can distinguish them on the clearest of nights. Yet, as Fray Junipero of Cadiz who taught me Catholic doctrine in my childhood once assured me, every one of them is numbered and registered and twinkles with a certain divine destiny. ‘If even the least of them were to be quenched, my son,’ he said, ‘an equivalent loss on earth would soon be observed.’

From where I knelt on the cold sacristy floor, before the image of Saint Francis, I asked dutifully: ‘Father, what moral are we to deduce from this?’

‘Little Andrés, my son,’ he answered, ‘the moral is as plain as the nose on your face. Even the most minute event that may to all appearances be wholly finished and done with, whether proceeding from a good intention or from a bad one, must necessarily, in God’s good time, have its effect upon the people concerned in it: an effect consonant with the quality of the intention—as grapes are fruit of the useful vine, and thistle-down flies from the thistle, food of asses.’

Fray Junipero’s philosophic doctrine was as memorable as his discipline was severe, and with this particular conclusion I have always been in perfect accord. All the troubles, for example, that occurred during the famous and terrible voyage across the South Seas which is the subject of this history may be said to have sprung, and spread like thistle-down scattered by the wind, from the tale of the Blind Girl of Panama. This tale therefore, though raw and indelicate, I will quote in full as I heard it, not indeed for your amusement (the Saints forbid!) but—by one of those paradoxes beloved and exploited by the schoolmen—for your moral edification.

On the morning of the fourth day of April, in the year of our Lord 1595, at Callao, the port of Lima where the viceroys of Peru reside, I stood with two companions in the waist of our flagship, the San Geronimo, a fine galleon of one hundred and fifty tons; and from the mastheads above us two royal banners of Spain and the pendant of General Don Alvaro de Mendaña y Castro fluttered bravely in the land breeze. This celebrated explorer, a nobleman of Galicia and nephew of a former Lord President of Peru, had been appointed to command our expedition, by royal letters patent signed by King Philip II himself. Our destination was the Isles of Solomon, which Don Alvaro had himself discovered twenty-seven years before, but which no one had visited since; our purpose, to colonize them. My companions were the valiant Ensign Juan de Buitrago, a scarred and grizzled veteran of many wars, and tall, hook-nosed, mild-mannered old Marcos Marin, the Aragonese boatswain.

‘That is very true, Don Marcos,’ the Ensign was saying. ‘Some women will never be put off, try how you may. I remember when I was a young soldier at Panama, billeted in the house of an ebony-merchant from Santander, a very respectable man whose name I have now forgotten… Shortly after my arrival, as we sat drinking in doublet and shirt, he said to me earnestly: “Don Juan, may I ask you to do me a kindness?”

‘“I am entirely at your disposal, host,” I said.

‘“It is this. In a garret of this house lives a beautiful girl, an orphan, who spends her days carding and spinning wool. Very industrious she is, and proficient at her work; but can do no other, because, poor creature, she is blind. This girl greatly desires to handle your arms and speak to you, for her grandfather who brought her up once served under the great Pizarro, and though a model of piety, she is always curious to hear tales of soldiers and camp life.”

‘“To refuse a blind orphan a few minutes of my long day would be uncharitable indeed,” I said. “I am ready to humour her this very moment, if you please.” With that I rose, made an armful of my accoutrements and told him: “Lead on.”

‘We went upstairs to a garret room where the girl sat spinning at the open window; and beautiful she was, by the eleven thousand virgins of Saint Ursula, with her pale skin and broad brow like the Madonna’s, her glossy hair, slim waist and rounded bosom. My host made us acquainted, and a few compliments and nothings were exchanged, when presently he was called away on a matter of business and she and I were left alone.

‘Well, first she asked permission to examine my armour; and I handed her my headpiece, my corslet and my tassets, which she tapped with her nails and stroked with her fingers, greatly admiring their lightness and toughness. Next, she reached for my Venetian scabbard and fingered it thoughtfully from end to end; she cried out with delight at the silver chasing which, indeed, was curiously intricate and graceful—as you can see for yourselves, for here is the very scabbard. Next, she drew my sword out a hand’s breadth or two and tried its edge with her little thumb—“as keen as a razor!” she exclaimed—and her finger-tips traced the fine Toledo inlay on the flat of it. Next, my Mexican dagger and its

copper scabbard with the turquoise studs. Next, my trusty arquebus, with its match; my powder-horn, my bag of bullets. Everything pleased this poor blind girl beyond expression. But then, then—’

Don Juan paused and his face, that had been serious, took on a droll expression between triumph and shame. ‘But then—?’ the Boatswain prompted him.

‘—But then: “Is that all, soldier?” she asked in tones of dissatisfaction.

‘“It is indeed all, daughter,” I replied. “Though I am heartily sorry to disappoint you, I have nothing else.” But some women will never be put off, try how you may. She came close up to me and her eager hands went all about me, deft as a Neapolitan pick-pocket’s, remorseless as a Venetian sea-captain’s when he searches his captive Turk for concealed jewels; and pretty soon she caught firm hold of a something. “Aha,” she cried, “my brave comrade, what concealed weapon is this?”

‘“Take your little hands out of the larder!” said I. “That is no weapon of offence: it is no more than a prime Bolognian sausage hanging from a hook against time of need.”

‘“Hanging?” she exclaimed with surprise. “But it hangs upside-down!” And then in a voice of deepest reproach: “Oh, noble Don Juan, would you tell lies to a poor blind girl, and an orphan too?”’

The intention of the tale cannot by any means be described as a good one, and its effect was altogether lamentable. At the very moment that the Ensign reached this climax, lowering his voice because Father Antonio de Serpa, the Vicar’s keen-eyed Chaplain was edging near, a boat drew alongside and the Colonel, Don Pedro Merino de Manrique climbed ponderously aboard. The Boatswain and I were so beguiled by the tale that we did not turn round, and what with the sailors’ singing and shouting, and a duet of carpenters’ hammers, it was excusable that the Colonel’s arrival should have escaped our attention; we supposed that a bum-boat had come with fruit, or perhaps the skiff that had been sent to fetch the laundry.

The Greek Myths, Volume2

The Greek Myths, Volume2 The Anger of Achilles: Homer's Iliad

The Anger of Achilles: Homer's Iliad Count Belisarius

Count Belisarius The Twelve Caesars

The Twelve Caesars Complete Poems 3 (Robert Graves Programme)

Complete Poems 3 (Robert Graves Programme) Homer's Daughter

Homer's Daughter The White Goddess

The White Goddess Goodbye to All That

Goodbye to All That Claudius the God and His Wife Messalina

Claudius the God and His Wife Messalina The Greek Myths

The Greek Myths I, Claudius

I, Claudius The Islands of Unwisdom

The Islands of Unwisdom Complete Short Stories

Complete Short Stories The Golden Fleece

The Golden Fleece They Hanged My Saintly Billy

They Hanged My Saintly Billy King Jesus

King Jesus Sergeant Lamb's America

Sergeant Lamb's America Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis

Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis Seven Days in New Crete

Seven Days in New Crete Proceed, Sergeant Lamb

Proceed, Sergeant Lamb Claudius the God

Claudius the God Wife to Mr. Milton

Wife to Mr. Milton The Complete Poems

The Complete Poems The Anger of Achilles

The Anger of Achilles Claudius the God c-2

Claudius the God c-2 Hebrew Myths

Hebrew Myths I, Claudius c-1

I, Claudius c-1 The Greek Myths, Volume 1

The Greek Myths, Volume 1